Special statue dedication edition

"Men in pursuit of justice must never despair."

Thaddeus Stevens, May 8, 1866

Stevens statue dedication, April 2, 2022

Adams County courthouse, Gettysburg, PA

In this issue:

I. Schedule of events

II. The story of Thaddeus Stevens statues

III. Gettysburg statue donors

IV. The new Gettysburg statue

V. Major statue donor

VI. Sculptor inspired by Thaddeus Stevens

VII. Why I admire Thaddeus Stevens

VIII. Proposal for statue in nation's capitol

230th Stevens birthday celebration and statue dedication

Friday, April 1, Lancaster, PA

10 a.m. to 11 a.m. -- Tour of Stevens house at corner of Queen and Vine Street, conducted by Thomas Ryan, chief executive of LancasterHistory -- Free

Noon to 2 p.m. -- Seminar at Thaddeus Stevens College of Technology, 750 E. King Street, Lancaster, PA. Ross Hetrick, president of the Thaddeus Stevens Society, will speak on Stevens and the movies, from villain to hero. Bradley Hoch, author of Thaddeus Stevens in Gettysburg, the Making of an Abolitionist, will talk about Stevens involvement in the Buckshot War of 1838 where the Pennsylvania state government was taken over by mob violence. The seminar is free, but seating is limited and registration at info@thaddeusstevenssociety.com is requested.

2 p.m. to 3 p.m. -- Tour of Archives room at Stevens College. Event is free but registration at info@thaddeusstevenssociety.com is requested.

4:30 p.m. to 5:30 p.m. -- Graveside ceremony at Shreiner-Concord Cemetery at Mulberry and Chestnut Streets, Lancaster. -- Free

6 p.m. to 8 p.m. -- Banquet at Stevens College, 750 E. King Street. $50 per person.

9 p.m. -- Public showing of video about statue and Stevens at Stevens College. -- Free

Saturday, April 2, 2022 -- Gettysburg

10 a.m. to noon -- Seminar at Gettysburg Hotel, Lincoln Square, Stevens conference room -- Free, registration required. Featured will be Bruce Levine, author of the new Stevens biography, and Fergus Bordewich, author of Congress At War, who will talk about Stevens's critical role during the Civil War. Presentations will be by Zoom. -- free, but registration is requested at info@thaddeusstevenssociety.com.

Noon to 2 p.m. -- Free period. People can see Thaddeus Stevens artifacts at 27 E. Stevens Street or visit the Seminary Ridge Museum, 111 Seminary Ridge. Say you are attending the statue dedication for a 50 percent discount. Gettysburg Licensed Town Guides are also available to give 90-minutes tours that include information about Lincoln, the civilian experience and Thaddeus Stevens. They can be contacted at www.gbltg.com or 717-253-5737.

2 p.m. to 4 p.m. -- Dedication of Thaddeus Stevens statue, 111 Baltimore Street. Audience gathers from 2 to 3. Speeches and dedication at 3 p.m. – Bring your own chairs. -- Free

4 p.m. to 6 p.m. -- Free period

6 p.m. to 8 p.m. -- Banquet at Majestic Theater, 25 Carlisle Street -- $50 per person.

9 p.m. -- Public showing of new documentary about the statue and Thaddeus Stevens. In lot behind Transit Station, 103 Carlisle Street. Bring your own chairs. -- Free

Sunday, April 3, 2022 -- Caledonia State Park, Intersection of Routes 30 and 233, near Chambersburg, PA

10 a.m. to Noon -- Economist William A. Darity of Duke University, author of From Here to Equality, will talk about Stevens and reparations. A. Kirsten Mullen, co-author of From Here to Equality, a folklorist and founder of Artefactual, an arts-consulting practice, will talk on, "Finishing the job Thaddeus Stevens and the true Radical Republicans started," an examination of the material basis for black Americans' full citizen rights which Stevens, Sen. Charles Sumner and abolitionist Wendell Phillips recommended consistently from 1861 to 1866. -- Free. A light lunch will be served.

1 p.m. to 3 p.m. -- Thaddeus Stevens Society business meeting and tour of park's blacksmith shop.

Zoom presentation of seminars are planned. Register at info@thaddeusstevenssociety.com

The story of Stevens statues

By Ross Hetrick, president of the Thaddeus Stevens Society

When Thaddeus Stevens died in 1868, there was no doubt that there would be statues aplenty to the man who helped save the American republic and set it on a course towards a more equitable society. Major newspapers devoted their entire front pages to his life, he laid in state in the Capitol Rotunda and 20,000 people attended his funeral in Lancaster, PA.

"Monuments will be reared to perpetuate his name on the earth," said Horace Maynard, a Tennessee congressman on the floor of the House of Representatives in 1868. "Art will be busy with her chisel and her pencil to preserve his features and the image of his mortal frame. All will be done that brass and marble and painted canvas admit of being done."

Yet, 154 years after his death, there is only one Stevens statue and that only went up in 2008 at the Thaddeus Stevens College of Technology in Lancaster, PA. And now a second one is slated to be dedicated on April 2 in front of the courthouse in Gettysburg where Stevens lived from 1816 to 1842. Since his death in 1868, there have been five attempts to erect Stevens statues – two successful and three failures.

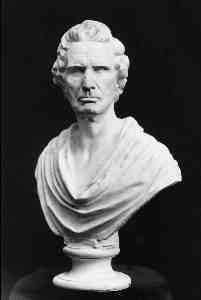

The first attempt to immortalize Stevens came from the beautiful and talented Vinnie Ream, a young sculptress, who was commissioned to do Lincoln’s statue that now stands in the Capitol Rotunda. Stevens took the 18-year-old Ream under his wing and got her the commission to do the Lincoln statue. In return, Ream did a plaster bust of Stevens with a Roman collar. While a picture of the bust exists, the actual bust has been lost to history.

Ream had a close relation with Stevens for the last three years of his life and in 1900 Ream offered to do a statue of Stevens in Lancaster, PA, for $25,000, according to an article in the New York Times. Then on January 12, 1903 there was a letter to the editor to the Lancaster Daily New Era from the Board of Trade that the group had been in correspondence with Ream, who wanted to do a Stevens statue under the condition the Board of Trade paid for casting and a granite pedestal, at a cost of about $5,000. The board agreed on the condition Ream give them a model of the proposed statue for approval. “In this she has failed, and a recent letter to her has remained unanswered.” said the Board of Trade and there was no further mention in newspapers of Ream’s desire to create a Stevens statue.

Sculptress Vinnie Ream, who had failed plans to do Stevens statue.

Plaster bust of Stevens done by Ream, but now lost.

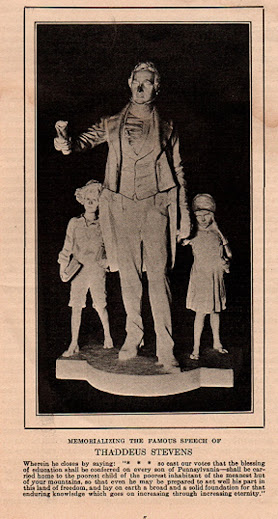

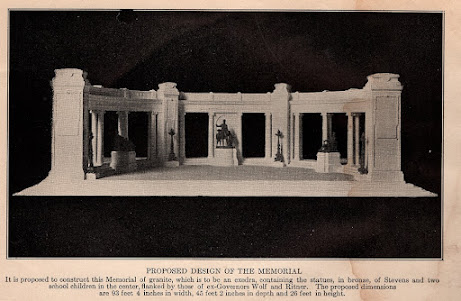

A much more ambitious effort came in 1909 when a group was formed to erect a public school memorial in Harrisburg, PA. Stevens would be included in this monument because of his famous 1835 speech, which turned back a repeal effort of the fledgling state school system. The memorial was to consist of a semi-circular colonnade with a bronze statue of Stevens at the center flanked by statues of governors George Wolf and Joseph Ritner, who implemented the public school system. On either side of Stevens would be a boy and a girl in tattered clothes clutching schoolbooks. The group, called the Pennsylvania Public School Memorial Association, hired an eminent sculptor, J. Otto Schweizer of Philadelphia, who prepared a plaster model of the monument. Schweizer also created seven sculptures for the Gettysburg battlefield, more than any other artist, including a larger than life statue of Lincoln as part of the Pennsylvania Memorial.

The group published a booklet soliciting funds that included a reprint of Stevens’s 1835 public school speech and Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address. They even had buttons made with a small image of the monument on it. In 1911 the group had a bill introduced in the Pennsylvania legislature to appropriate $100,000 for the project. The bill made it through the legislature only to be vetoed by Gov. John K. Tener in 1913. He gave a rather strange reason in his veto message, saying the planned location could not be prepared before the next session of the legislature. Then in a non-sequitur, he said he was also vetoing the bill because of insufficient funds “to the actual maintenance of public schools.” So because the legislature wouldn’t provide enough money for public schools, they wouldn’t get money to build a monument to public schools.

Model of Stevens statue that would have been part of public school monument.

Public school monument model proposed in 1909 that included Stevens statue.

Button produced by school memorial group.

It would be more than another 90 years before another effort to erect a statue to the Great Commoner. And during much of that period, Stevens’s reputation was systematically smeared by proponents of the “Lost Cause” mythology that glorified the Confederate cause. The high point of this effort was the publication of the Clansman, by Thomas Dixon in 1905, and the 1915 movie based on the book, Birth of a Nation. Both the book and movie demonized Stevens for advocating for black rights while making heroes of the Klu Klux Klan for terrorizing southern blacks.

But by the 1970s, Stevens’s greatness was being rediscovered and by the early 2000 an effort was underway to erect a monument to Stevens at the Thaddeus Stevens College of Technology in Lancaster, a school founded on a bequest in Stevens’s will. The effort was headed by college president William Griscom and Alex Munro, executive director of the college’s alumni association.

Dedicated on Stevens’s 216th birthday on April 4, 2008, the statue has Stevens sitting in a Congressional style chair of the period. Steven’s legs are crossed with his left clubfoot pointed forward as if to say disability is nothing to hide. Next to him is a young man symbolizing all the people who have been helped by the Great Commoner, both past and present through the school he helped found. Stevens statue at Thaddeus Stevens College of Technology.

But despite this great victory in recognizing Stevens’s importance, the following years were followed by disappointments as far as statues were concerned. In 2009 the Thaddeus Stevens Society was contacted by the development company Akridge in Washington, D.C. to support its plans to redevelop the historic Stevens school in Washington and to build an adjoining commercial building. To gain approval from the D.C. government, Akridge proposed including a a statue of Stevens and a story wall about the Great Commoner. The Society wrote letters of support for Akridge’s proposal, which were submitted to the Washington, D.C. government. After several years, Akridge plans were approved and the commercial structure was built and the school redeveloped, but there was no statue. Akridge blamed the D.C. bureaucracy for nixing the statue, but despite being in regular touch, Akridge never notified the Society of any hearing where the group may have been given a chance to defend the statue.

The Thaddeus Stevens school, which had been closed since 2008, was reopened in 2020 as an early learning center. Included on the campus is a perforated sheet of metal in the outline of Thaddeus Stevens with these words next to it: “ . . . A humble tribute of grateful remembrance to the late Honorable Thaddeus Stevens . . . the earnest champion of free and equal school privilege for all classes and conditions.” The Board of Trustees of Colored Schools of Washington and Georgetown in honor of Thaddeus Stevens 1792-1868

Perforated metal sheet at Stevens school in Washington, D.C. instead of statue. Another disappointment was in 2015 when Gettysburg College erected a statue in front of Stevens Hall. But the statue was not of Thaddeus Stevens, who the building was named after, but of Abraham Lincoln. This reflects the college’s constant emphasis on Lincoln, who played no part in the college’s history, while giving little attention to Stevens, who helped to establish the college and spent 34 years on its board of trustees.

But the incident did spur the Thaddeus Stevens Society to launch a campaign to raise $55,000 for a Stevens statue in Gettysburg, where he lived from 1816 to 1842. The effort reached its goal in 2018 when Michael Charney of Ohio pledged $39,500. A retired teacher and union official, he is a great admirer of the Old Commoner and even named a past dog Thaddeus.

After the goal was reached, a nationwide search was launched to find a sculptor and Alex Paul Loza, a Peruvian native who lives near Chattanooga, TN, was selected from 20 proposals. In preparing his submission, Loza researched Stevens and became a great admirer, resulting in him fashioning a small model of a dynamic Stevens holding a copy of the 14th Amendment to the Constitution, one of his greatest works.

Then in 2021, as Loza was nearing completion of the statue, the Adams County commissioners approved an agreement with the Stevens Society to install the statue in front of the county’s courthouse on Baltimore Street in Gettysburg.

While this statue is a great accomplishment, there is so much more to be done. Restoration of Stevens’s house in Lancaster, PA, has been stalled for more than a decade. But planning and fundraising for the project started again in recent years and the project may be completed by the middle of this decade. There is also a great need to stabilize the condition of the Lancaster cemetery where Stevens is buried.

But as the Gettysburg statue campaign has shown, the determination of Stevens admirers will continue unabated and will result in Stevens sites being restored and monuments raised to the Great Commoner.

Gettysburg statue donors

Michael Charney John Lovell

Ross Hetrick Angela Powell

Bernistine Nabia Little Hilda Nitchman

Donald & Bobbie Gallagher Donald Rhoads

Steven Livengood Bradley Hoch

Wesley Foltz Frank Ninivaggi

Dale Hetrick Janice Smith

Carolyn Quadarella Beverly Palmer

Craig Howell Sam Mecum

Merry Stinson Ruth Hernandez-Siegal

Patricia J. Longenecker Marguerite Fabert Wilson

Al Massey Janet Landon

Randy Harris Rosalie Moore

David Atkinson Patricia E. Roche

Veronica Brestensky Kathleen Brestensky

Janice Grove Thomas Grove

Terry Webb

John Buchheister, The Maryland Sutler

Thaddeus Stevens College of Technology Alumni Association

Susan Swope and Shirley Tannenbaum

Robin E. Sarratt and Thomas R. Ryan

LancasterHistory

The new Gettysburg statue

"Men in pursuit of justice must never despair." Thaddeus Stevens, May 8, 1866

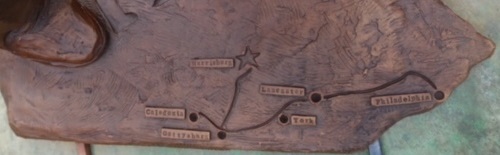

The new Gettysburg bronze statue is titled, "Men in pursuit of justice must never despair," a quote of Thaddeus Stevens. It is Stevens's height of 6 feet and he is clutching a copy of the 14th Amendment, one of his greatest achievements. He is standing on a base in the shape of Pennsylvania.

A wayside sign next to the statue highlights Stevens's achievements and describes the map on the statue's base. A QR code is included to provide more information on the Thaddeus Stevens Society's webpage.

Map on base shows important locations in Stevens's life: York, Gettysburg, Harrisburg, Lancaster, Caledonia and Philadelphia.

Longtime Stevens admirer provides much of the money for Stevens statue

Michael Charney is the perfect example that there are people throughout the United States who recognize the greatness of Thaddeus Stevens and who are willing to make sacrifices to promote his memory.

The Thaddeus Stevens Society launched a fundraising effort in 2015 to raise $55,000 to erect a statue in Gettysburg. By 2018 the Society had amassed pledges of $15,500. Nice, but still far away from the goal. Then Michael, who lives in Ohio, stepped in. Already a lifetime member of the Society, he offered to pay the remaining $39,500, which made the statue possible.

A retired teacher, union official and longtime social activist, this is why he did it in his own words:

"Thaddeus Stevens is unlike any politician today. He did not consult the latest political opinion poll to determine what he would do.

Instead, Stevens held a principled anti-slavery position throughout his career.

But Stevens was more than an anti-slavery advocate. He was a pragmatic politician with a keen sense of overall strategy combined with a meticulous tactical sense to move his anti-slavery agenda.

He successfully pushed President Lincoln to a step by step support for using "colored" troops to fight for their own liberation, and use the role of his office to embrace the 13th Amendment, an important part of the Radical Republican program championed by Stevens.

And Stevens understood the importance of economic as well as political equality by proposing breaking up the largest slave plantations and distributing the land to the newly freed people.

That is why I named my dog Thaddeus so I could communicate the crucial role Thaddeus Stevens played in the struggle for African American political and economic equality."

Thanks so much Michael, you have done a great service to the memory of Thaddeus Stevens along with all the other members and supporters of the Thaddeus Stevens Society.

Michael Charney, retired teacher and union official

Artist inspired by Thaddeus Stevens

When artist Alex Paul Loza made a proposal in 2019 to create only the second statue of Thaddeus Stevens, he was surprised he had never heard of him

"The more I read about Stevens, the more I began to connect and related with him," Loza said. "And similar to Stevens's mother, my mother, Amalia Villafranca, relied on her faith, resilience and perseverance to support our household."

"I learned that Stevens utilized his knowledge and political influence to serve, defend and empower oppressed communities to bring equality and justice. As an artist, I use my artistry and voice to serve and empower unrepresented communities and tell their stories," he said.

Loza said his statue not only celebrates Stevens's life, but "reflects his tenacity and admirable beliefs that can inspire individuals to make positive changes in their communities by creating safe spaces and building alliances."

He is involved in many art projects in the Chattanooga, TN area, where he lives with his wife, Jocelyn Avendano-Loza and their two daughters, Emie, 11, and Ellie, 7.

Loza recently was commissioned to create the first ever life-size bronze sculpture of "Little Debbie" of snack food fame.

Sculptor Alex Paul Loza in his studio.Why I admire Thaddeus Stevens

Below are essays by Thaddeus Stevens members and others on why they admire Stevens.

For me, "The Great Commoner" says it all. He was a champion for the common good! I propose making him the patron saint of activists! He certainly is a role model for public servants. We need to follow his example of reaching out and speaking for the marginalized. I take great pride that Thaddeus Stevens was a part of our community!

Kathleen Brestensky, Gettysburg, PA

Thaddeus Stevens: Equality For All, and Equality Above All

I admire Thaddeus Stevens because he dedicated his life to relentlessly advocating for racial equality and freedom—despite significant resistance and personal cost—and he did so with courage and conviction.

Born in 1792 and possessing a zeal for racial equality, Stevens was seemingly before his time. But he pulled history’s time forward, spurring the United States to more tangibly provide the protections and rights set forth in our country’s founding documents. He implored Lincoln to declare emancipation and his Congressional colleagues to pass the 13th Amendment, in addition to authoring the 14th Amendment.

With these endeavors, he translated lofty ideals into real freedom, equality under the law, and civil liberties for our most oppressed compatriots. He incurred steep financial losses and stiff political

pushback throughout his career due to his efforts, but his vision never wavered. Stevens also advanced the cause of equality by increasing access to education. He championed public

education in Pennsylvania, beating back a repeal bill poised to cripple the public school system, and was instrumental in establishing Gettysburg College. Thanks to his work, countless youth enjoyed upward mobility and better lives for themselves and their families.

In his death, as in his life, Stevens promoted equality, choosing to be buried in an integrated cemetery and concluding his epitaph with, “Equality of Man Before His Creator.” He was a singular force in

bending the arc of our country’s history more toward justice.

Dylan Waugh, Parkton, MD

What I have learned about the late Congressman Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania as a member of the Thaddeus Stevens Society has created an insurmountable admiration for him for the following reasons:

Before President Abraham Lincoln, Congressman Stevens was deeply concerned about abolishing slavery. He initiated strategies that helped President Lincoln to bring about the end of the Civil War by mean of the Emancipation Proclamation, and the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution that actually abolished slavery on January 31, 1865.

After the death of President Lincoln, Thaddeus continued to help right the wrongs of the country by passing the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution, which made all persons born or naturalized in the United States citizens. Moreover, he paved the way for the Fifteenth Amendment establishing voting rights.

Thaddeus Stevens strongly believed in equal rights for all, and he illustrated this in his death by being buried in an integrated cemetery and having an epitaph written on his tomb that reflected what he stood for in life.

In conclusion, the more I read about human and civil rights actions taken by Congressman Thaddeus Stevens from the Thaddeus Stevens Chronicles written by the president of the Society and lectures provided, as well as from the lecturers’ books, my admiration for the late congressman becomes even stronger.

Bernistin Nabia Little, Franklin Park, NJ

Thaddeus Stevens and Support for Free Public Schools

It goes without saying, that Thaddeus Stevens was a champion of funding for public education. In April of 1835 the Pennsylvania House of Representatives was considering to repeal a law that

established public education in Pennsylvania. Stevens argued against the repeal. “I will attempt to show that the law is salutary, useful and important; and that, consequently, the last Legislature acted wisely in passing, and the present would act unwisely in repealing it.” (The

Selected papers of Thaddeus Stevens, 1997 p.57, University of Pittsburgh, edit Palmer and Ochoa)

Stevens elaborated on the position. He argued that free education would elevate the public in the scale of human intellect. Free public schools would benefit society in general. For Stevens the public school stood as a bastion against the establishment of a pauper class and provided mobility for all – sentiments that likely grew out of the poverty he experienced as a youth in Vermont. This was followed up with Stevens’s reference to schools of antiquity: “There all were instructed at the same school; all placed on perfect equality, the rich and the poor man’s sons . . .” (Ibid p. 59).

After addressing taxation in support of public schools and other issues, Thaddeus Stevens convinced the Pennsylvania House of Representatives to defeat the repeal. It is amazing that a

public servant that spent a lifetime supporting public schools is not more broadly recognized. Stevens’s name was maligned along with other abolitionists and Republican Reconstructionists by late 19th century racist writers like William Archibald Dunning and his supporters in the South and at Columbia. The time is right to expound on the positive accomplishments such as public education made by Thaddeus Stevens.

Mike Hall, Conroe, TX

My Intersections with Thaddeus Stevens, Exceptional Public Servant

A borough resident for twenty six years, Thaddeus Stevens stands historically as one of its most important citizens. His championing of public education while representing this county in the state

legislature alone would warrant our admiration. Stevens’ critical role in shepherding the thirteenth and fourteenth amendments fundamentally improved our nation to a greater extent. Unfortunately, his scrupulous nature is often missed in light of his typically rather abrasive demeanor and piercing wit. While these qualities did not often make Thaddeus Stevens the favored guest in high society, they served as critical traits of the Great Commoner that were conjoined with his ability to earn such critical victories as a free education for all in the commonwealth, freedom for the enslaved, and equal protection of the laws for all of us.

I am a product of the public education system that Stevens preserved, and having graduated from Gettysburg College, which he helped to found, now teach in that very system a few miles north in

Biglerville. Stevens’ portrait occupies a prominent place in the front of my classroom, and each year I get to share the story of his perseverance in securing the thirteenth and fourteenth amendments with a new group of students.

I am very proud to serve as the president of the Gettysburg Borough Council this year, two hundred years after Thaddeus Stevens served the citizens in the same role. My home rests between

Stevens Street and Stevens Run. Stevens once owned the land, and conveyed it to Adam Doersom and Nicholas Codori, who conveyed it to John McClellan, who sold it to the Barbehenn family, who built our house. I often stroll past the site of Stevens’ former office on Chambersburg Street, and of course the site of the old courthouse in the square, where he argued many important cases.

Many Americans are unfortunately quite ignorant of the role that Thaddeus Stevens played in securing and preserving many of the rights that they enjoy today. I am blessed to have a robust

understanding of his contributions, and consider it part of my duty to ensure that his legacy is known by our children through my teaching. While I know that I will never serve as critical a role as Mr. Stevens

did in the history of our nation, I hope that my own service on borough council will leave a lasting positive impact on our community.

Wesley K. Heyser, Gettysburg, PA, Borough Council President

“Thaddeus Stevens, Prescient and Principled: An Appreciation”

I hold Thaddeus Stevens in high esteem for his steadfast belief in the equality of women and men—black and white—expressed in his speech and his actions. For Stevens, black lives mattered. He also understood that for blacks to have full citizenship rights “the whole fabric of southern society must be changed.” Nothing short of “de-Confederatization,” a “radical reorganization of southern institutions, habits, and manners” would have to occur.

1. A “true republic” only would become a reality if the nation—and not just the south—accepted federal legislation and embraced a sustained national campaign that included enforcement by the military and the courts.

2. Part of the Radical Republican minority who warned against embracing Andrew Johnson, a political chameleon from “one of those damned provinces,” as Abraham Lincoln’s running mate,

Stevens pointed out the contradiction inherent in affirming a pro-black rights position while leaving black suffrage out of the party platform at the National Union Party in 1864. The work Thaddeus Stevens outlined remains to be done. It is 156 years overdue.

A. Kirsten Mullen, Chapel Hill, NC

A PROPOSAL FOR NATIONAL RECOGNITION OF THADDEUS STEVENS

By Steven Robert Howard

One of the highest honors the United States of America can bestow is installing a statue of a citizen in the National Statuary Hall collection in the US Capitol Building. There are only 100 statues donated by the states which are each limited to two statues. This article proposes that a statue of Thaddeus Stevens be installed in that national pantheon.

The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania has donated statues honoring Robert Fulton of steam boat fame and John Peter Gabriel Muhlenberg, an American Revolutionary War hero who was also an early US Representative and US Senator from Pennsylvania.

Thaddeus Stevens is one of America’s leading advocates for racial equality and national indivisibility, and as such is eminently qualified for the national distinction that comes with having a statue in the US Capitol Building. Thaddeus Stevens has the requisite deep and

enduring connection to Pennsylvania. Stevens resided in Pennsylvania for over 50 years. Although born in Vermont, at age 23 Stevens moved to Pennsylvania where he resided for the rest of his life with intermittent stints in Washington, D.C. in order to better serve his Pennsylvanian constituents. Stevens was a member of the US House of Representatives from Pennsylvania from 1849 to 1853 and then again from 1859 to his death in 1868. Stevens was the Chairman of the all-important House Ways and Means Committee for 4 critical years during the Civil War from 1861 to 1865. Stevens’s law offices were in Gettysburg and Lancaster, PA. Stevens is buried in the Shreiner-Concord Cemetery in Lancaster, PA.

This proposal to install a statue of Thaddeus Stevens in the US Capitol Building has the obvious challenge that one of the two Pennsylvania-donated statues would have to be removed. While Robert Fulton undoubtedly enjoys much broader national and international recognition than John Muhlenberg, and on that basis could presumptively remain in the pantheon, on closer

examination, Fulton has only a tenuous connection to Pennsylvania. Fulton was born in Lancaster, PA but moved to England at the tender age 21, never to reside again in Pennsylvania. When Fulton returned from England, he took up residence in New York City and was buried there in the Old Trinity Churchyard Cemetery close to the grave of another famous New Yorker, Alexander Hamilton.

In contrast, John Muhlenberg and the extended Muhlenberg family, have a deep connection to Pennsylvania. Born in Trappe, PA, Muhlenberg resided in Pennsylvania for most of his life. Muhlenberg was a Lutheran minister following in his father’s foot steps who founded the Lutheran Church in Pennsylvania. Muhlenberg served as a Major General in the American Revolutionary War and commanded the First Brigade of Lafayette’s Light Infantry. Muhlenberg fought in the battles of Brandywine, Germantown, Monmouth County and Yorktown. After the Revolutionary War, Muhlenberg was elected to the US House of Representatives and the US Senate from Pennsylvania.

As a practical consideration, given Muhlenberg’s extensive connections to Pennsylvania, one can assume greater resistance to removing his statue from the Capitol, than removing Fulton’s statue. While both Fulton and Muhlenberg are worthy of the honor of having their statues in the Capitol, Fulton continues to be regaled with a statue in the Library of Congress, 7 counties in the United States named after him, 11 towns, 5 ships in the US Navy, and four

important sites in New York City.

A federal law passed in 2000 authorizes the replacement of statues in the National Statutory Hall collection. To date 9 states have replaced one of their statues. Nine additional statue replacements are currently pending in state legislatures.

The replacement process starts with citizens’ written petitions to the Pennsylvania General Assembly to honor Thaddeus Stevens and relocate the Robert Fulton statue. The Pennsylvania House and Senate pass a law signed by the Governor that names Thaddeus Stevens to be commemorated, cites his qualifications, and establishes a commission to select and pay a sculptor. The Architect of the Library of Congress is authorized by federal law to work with the

state commissions to arrange for a location of the statue in the Capitol after it is unveiled in the Rotunda.

We can expect significant opposition to this proposal from many quarters and getting the authorizing statute signed into law will take considerable time and effort. Some statue replacement efforts like Harriet Tubman in Maryland have been defeated. Nine have succeeded, and more are expected to succeed in the near future. Thaddeus Stevens and our national commitments to racial equality before the law and our country’s indivisibility are worthy of the

effort.

"He never flattered the people; he never attempted to deceive them; he never 'paltered with them in a double sense;' he never courted and encouraged their errors. On the contrary, on all occasions he attacked their sins, he assailed their prejudices, he outraged all their bigotries; and when they turned upon him and attacked him, he marched straight forward, like Gulliver wading through the fleets of the Lilliputians, dragging his enemies after him into the great harbor of truth." Rep. Ignatius Donnelly, MN, 1868